There is a man in your walls. He listens to everything you do. He follows you around, even if you leave your house. If you started feeling that way, you would probably consult a psychiatrist or psychologist. But what if they told you that you are actually not paranoid, but that chances are quite likely that there indeed is someone watching your every step? This realisation adequately describes the state of mind that people in the GDR used to live with. But who are these people watching your every step, and how does it affect those who spend their entire day in the lives of others? Das Leben der Anderen asks exactly that question and reminds us of the redeeming power of art in the face of oppression.

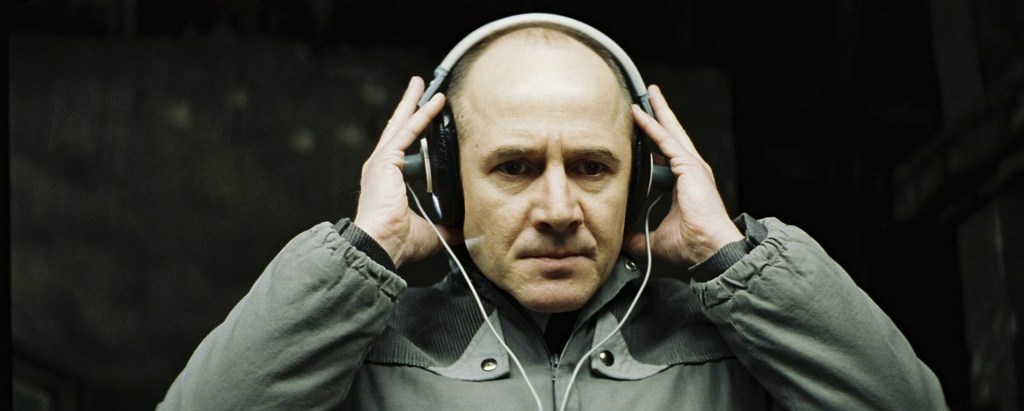

Das Leben der Anderen follows Gerd Wiesler, who is a dedicated Stasi agent in Berlin in 1984. Tasked with monitoring the seemingly regime-loyal playwright Georg Dreyman, as well as his lover Christa-Maria Siedland, he starts to sympathise with the couple and questions the morality of his own choices. Dryman becomes disillusioned after his blacklisted mentor kills himself and secretly writes an article about high suicide rates in the GDR. This starts a game of cat and mouse. The Stasi employs more and more agents to persecute Dryman, whilst Wiesler, moved by Dryman’s humanity and passion, subtly starts to manipulate the investigation.

Directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, Das Leben der Anderen employs a slow, restrained and observational style that reflects Wiesler’s role as a silent observer. Shots are static and often shot in close-ups or mediums, giving the movie a feeling of claustrophobia within the movie’s confined spaces. Tension builds steadily, as the slow pace of the editing emulates the meticulous nature of surveillance. It also commands the attention of the viewer, as shot transitions seem more important the less they are used. The film builds a strong visual parallel between Dreyman’s life and Wiesler’s reaction to it, almost simulating it upstairs.

Von Donnersmarck explores notions of paranoia, control and loss of privacy. The perceived omnipresence of the state is felt in every action characters undertake, every thought and conversation, and every instance of private life can lead to persecution. The state’s power is constructed through surveillance, infringing on the autonomy of the individual. And we, as viewers, are complicit in this surveillance.

Just like Wiesler, we spy on Dreyman and his lover, follow their every move, and start to sympathise with his struggles. The movie reminds us of the redeeming power of art, as the exposure to love, passion and resistance against impossible odds inspires Wiesler to question his actions. Wiesler’s redemption becomes our redemption. We are reminded that our passion for movies is more than just the act of voyeurism. Art becomes a form of resistance to the dehumanising force of oppression, a call to action, a reminder that our actions hold meaning.

I may not have lived during the GDR, nor do I come from the eastern parts of Germany, but still, I relate to the dullness that Dreyman is resisting. It addresses something that has pressed me since I was a kid, the philistine conformity of everyday life. It definitely inspired me to be a better person and to stand for my beliefs.

When Wiesler, through the hidden microphones in Dreyman’s walls, listens to Beethoven’s Sonata for a Good Man, it marks his recognition of guilt and his road to reconciliation. Through Dryman’s life, he had realised his agency. It reminds us, as cinephiles, that we must find our own agency too, we who spend so much time in the lives of others.